8 min read

Beyond the "Why": 5 Coaching Secrets to Unlock Curiosity in Leadership

When my daughter was 17 months old, she discovered a superpower: the word “Why?”For the next two years, it was her response to almost everything.

Develop leaders, strengthen executive teams and gain deep insights with assessments designed to accelerate trust and performance.

Transform how your leaders think and perform with keynotes that spark connection, trust and high-performance cultures.

Explore practical tools, thought-leadership and resources to help you build trusted, high-performing teams.

Trustologie® is a leadership development consultancy founded by Marie-Claire Ross, specialising in helping executives and managers build high-trust, high-performing teams.

8 min read

Marie-Claire Ross : Updated on March 31, 2021

Despite what collaboration software experts would have you believe, few companies have big issues with trust within teams. When it comes to improving trust within organisations, the number one issue I have found is collaboration across teams.

It’s not just poor performing businesses that have this problem. Even successful companies have this issue at some level. Where there are silos between business units, functions, divisions or geographies it creates enormous productivity problems that are often ignored.

According to a study in Harvard Business Review, 9% of managers feel that they can rely on cross-functional colleagues all of the time. While 50% say they can rely on them most of the time. More importantly, managers say they are three times more likely to miss performance commitments because of insufficient support from other units than because of their own teams’ failure to deliver.

These are costly issues. According to a study by Tania Menon and Leigh Thompson in Harvard Business Review, silos causing teams to miss valuable insights from people in other areas, costs on average $US7,700 a day.

As organisations get bigger through organic growth or acquisitions, consolidation becomes an important value creation strategy to provide economies of scale and reduce duplication of effort. Operating in a borderless and integrated fashion across geographies and functions improves growth and adaptability. Back in 1994, when Lou Gerstner took over IBM one of his major tasks to help the failing company was to reduce billions of dollars in expenses through consolidating global functions and to train staff to collaborate across borders and functions. Achieving this goal helped turn IBM around in a spectacular fashion.

But it’s rare. Even today, few large organisations do this well.

When a successful group has been working together for some time, they quite easily form an in-group bias that makes it difficult to build trust and co-operate with different groups. Groups that feel threatened tend to close ranks and become more internally cohesive and exclude outsiders. It creates a vicious cycle of distrust and competitiveness between departments. Team members weigh up whether they can trust other team members based on a tallying up of similarities and differences. When employees can’t see that working together enables everyone to win, it becomes too easy for differences, rather than similarities to shape trust relations.

Even in a healthy culture, employees may want to co-operate, but they can’t seem to despite themselves. Their team’s goals and priorities always get in the way. It means they often break their promises; missing deadlines, going over budget, failing to adhere to specifications or customer expectations.

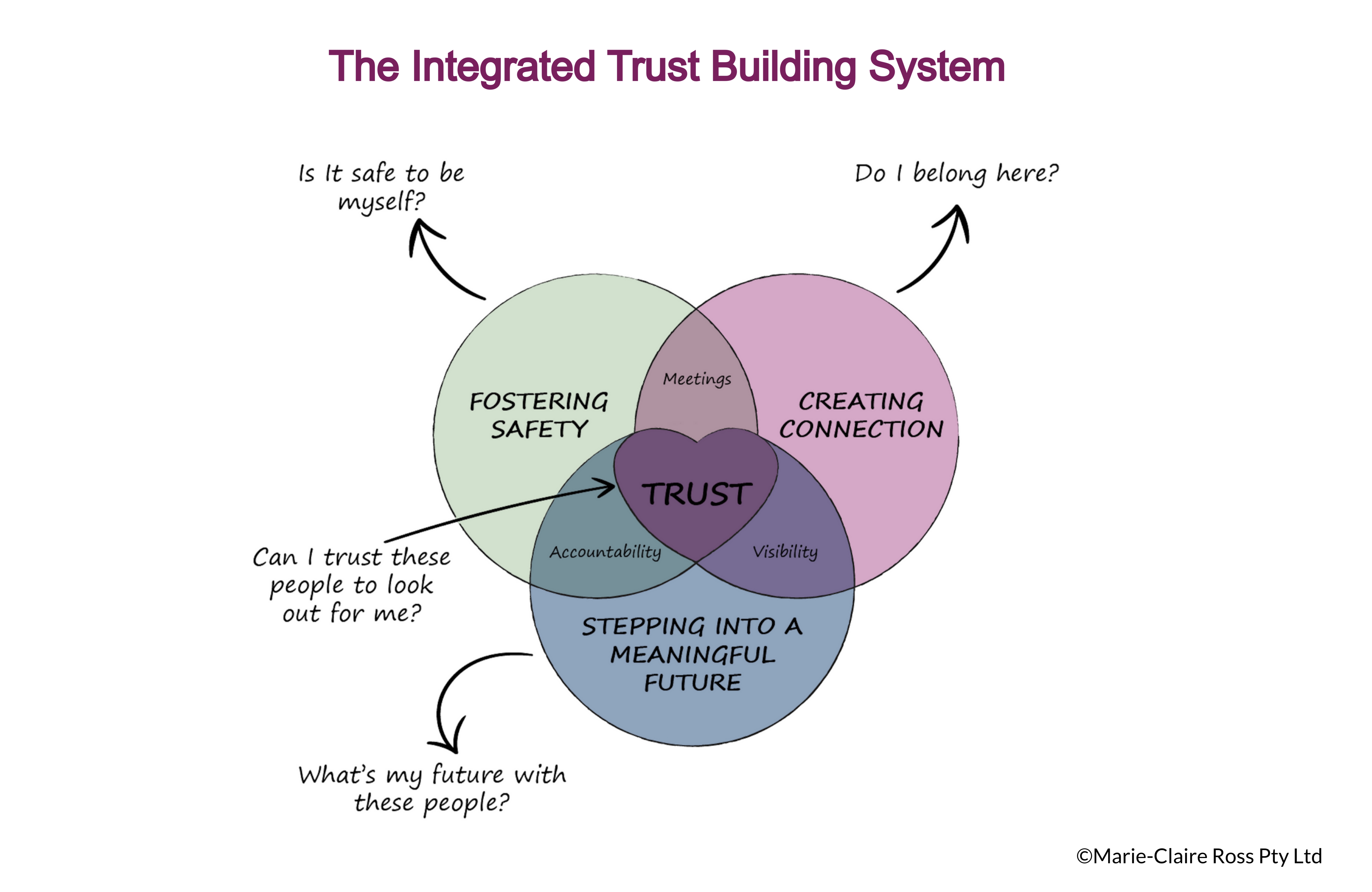

Before we launch into how to attack this pervasive problem, let’s get clear on what trust really means within an organisation.

A definition I have created to bring leaders into alignment is:

The ability for everyone in an organisation to confidently rely on (and predict) that others will do the right thing.

Marie-Claire Ross

At it’s most basic form trust is a promise that an organisation’s people will deliver on time, to the right level of quality and on budget without hurting the environment, company brand or other people. The proliferation of promises and deliverables are seemingly endless. Customers rely on organisations to provide high quality products or services. Finance depends on the sales team to put their travel expenses in on time, so finance can deliver the end of month financials. Frontline staff need to feel that head office cares about them. Throw in interdependencies, flawed systems and multiple stakeholders and it’s tough to unravel how to get different groups to trust one another.

Getting different functional teams to collaborate and trust each other is not the only challenge.

In a world of fast change and complex business problems, appointing a cross-functional team comprising different subject matter experts is the way to solve complex issues. Unfortunately, a study by Lynda Gratton and Tamara J. Erickson reported in Harvard Business Review found that the ability for these teams to collaborate were actually hampered by diversity, large team size, virtual participation and even high education levels.

Yep, you guessed it. The very characteristics required for a high performing team actually undermine it. The greater the proportion of highly educated specialists in a team, the more likely the team fell into unproductive conflicts. The higher the proportion of people who didn’t know anyone else in the team and the greater the diversity, the less likely members exchanged ideas and information. But not only that team sizes over 20 reduced co-operation, as well as team members working in different offices.

Given the value creation benefits of cross-team collaboration improving an organisation’s ability to co-operate is a no-brainer. Gathering experts from a variety of teams and disciplines provide a fresh perspective, deep insights and innovation. Of course, expecting teams to work together seamlessly is practical in theory, but in reality, often doesn’t go to plan.

Another Harvard Business Review report by Behnam Tabrizi found that 75% of cross-functional teams fail because of unclear governance, a lack of accountability, goals that lack specificity and from the organisations’ failure to prioritise the success of cross-functional projects.

Given how important it is to optimise collaboration across your organisation, let’s go through the steps, we do, to help teams improve their ability to deliver on their promises.

People feel greater trust and empathy toward people who are similar to themselves and are part of the same social circles. A clear sense of purpose, values and mission connect everyone together through being able to collectively see the meaning of their work. It’s how you get a diverse group of people aligned.

The central pillar for building trust is a corporate purpose that’s defined by a genuine commitment to the social good. Purpose is what a company stands for and creates value for employees, customers and society.

A social purpose provides employees with the context they need to understand how their work makes a difference to the world. It lets everyone know how much the organisation cares, which in turn makes them less likely to believe the organisation just exists to make money. It makes sense because we’re more likely to trust a company if we can see evidence of consistent action and behaviour that indicates good intent.

Focusing on purpose rather than profits is what builds business confidence and therefore, trust.

A meaningful purpose and values embedded in an organisation create a strong workplace culture that is geared toward cultivating the human instinct to bond. The challenge is to ensure that it unifies the total workforce together, and provides meaningful in-group status, rather than allow employees to drift into silos and bond only with those in their department.

It also means pivoting the organisation towards a stakeholder approach that focuses on the needs of different groups when making decisions such as employees, customers, local communities, stockholders and debtors, rather than the more traditional shareholder perspective which is centred on the organisation existing to maximising the wealth of its owners.

Typically, when companies attempt to fix trust issues they focus on symptoms but fail to improve the underlining systemic issues. To improve trust and ultimately performance, there needs to be a review of systems and how gets work done.

This requires reviewing the organisational design that communicates information on roles and accountability, the authority between people and how work and information are organised, shared and delivered.

Improving how profit or credit for success is shared among internal collaborators becomes important.

If an organisation wants to foster group collaboration, it must minimise the risks of collaboration and actually reverse the risk. This means reducing the risk for teams to collaborate by restructuring rewards to incentivise the correct collaborative behaviours. That is by penalising leaders that compete with each other or avoid collaboration when it would hurt the company. As well as ensuring rewards are based on the work of the collective and not a team or individual.

In addition, compliance, HR and financial systems need to be reviewed in order to remove red tape and improve fairness and transparency.

Once the purpose is clear and systems are addressed (or under progress), then it’s time to clearly specify what behaviours, expectations and attitudes are required to support collaboration. Rather than hoping that collaboration will occur naturally, the best practice is to create a cross-functional strategy that coincides with the strategic growth plan.

Where trust often breaks down between departments is where the complexity of misaligned interests is not acknowledged, much less dealt with. It requires a collaborative approach to empower groups to make the decision as to whose interests should be best served when there are competing agendas.

This responsibility belongs to the CEO to prioritise cross-functional collaboration and remove roadblocks. As well as promoting a “one firm” focus that moves people beyond narrow self-interests, in order to commit to common goals. The CEO must constantly reinforce the importance of being part of an organisation beyond geographical, business unit or functional identity. Prioritising the success of cross-functional projects involves creating a clear strategy that:

How executives model collaboration with each other is critical. One mid-sized organisation I worked with had a head of operations who didn’t like the head of sales feeling threatened by their young age. The result was an important customer delivery was missed because operations didn’t let sales know they were waiting on a shipment of chemicals. Misplaced loyalty meant that all of the operations team and sales team wouldn’t talk to each other for fear of upsetting their respective bosses.

Good leadership (and emotional maturity) is essential. Leaders must be accountable to deadlines and demand high-quality deliverables from end-to-end. They must be accessible and open to being notified of schedule changes or quality issue by their direct reports. If employees don’t have the power to fix these errors, leaders must step in and go direct to the department leader to sort out bottlenecks that are holding up workflows.

The most trusted leaders navigate this territory by carefully thinking in terms of integration and alignment of interests within the overall strategy of the organisation.

Furthermore, the company’s top executives must invest time building and maintaining social relationships throughout the organisation.

In addition to the overall strategy for collaboration for the organisation, each team must be responsible for their own team charter that specifies the purpose of the team and the problem to be solved, but also how they will collaborate with other teams.

What I have found is that team members typically don’t think about their responsibilities to other teams. It’s very common for team members to complain about other departments without considering how they let other teams down. In a recent workshop, I was running to improve trust across teams, a finance administrator proudly told the team that they had a 100% success rate of delivering. When the CFO glumly mentioned five deliverables that had been missed, the team suddenly realised how important their role was in the smooth functioning of the organisation. Such a process provides much-needed context about how everyone in a company relies on each other.

A typical charter includes the purpose, the team values, roles and responsibilities, how each team member prefers to receive and provide communication, budgets, resources, goals, timelines, cross-functional deliverables and agreements.

Given that most of us come from an education system that rewards being the best and brightest, collaborating isn’t always easy for some employees.

Human resources must recruit those with the ability to collaborate and remove those who let their self-interested behaviours run wild.

Employees must be taught techniques to build relationships, have honest and open conversations, align stakeholder requirements and resolve conflicts. Leadership programs must also champion creating high trust and emotionally intelligent leaders.

In addition, research also points to the need for HR to support informal community building. Organisations with strong collaboration, typically have an HR team that has made a significant investment in either collaborative training and initiatives supporting connection.

Commonly, companies separate workers based on their subject expertise. It makes sense to have those working together with the same goals and priorities. After all, we all feel comfortable working with people who are similar to us. However, it creates strong tribes that often unintentionally dislike working with other colleagues. Employees tend to work around, or against, each other.

Creating a unified culture is a powerful value creator that removes unnecessary costs. When departments don’t trust each other to deliver, issues with supply and demand inevitably lead to missing customer deadlines.

It requires the CEO to drive a strong one-firm focus, in order to improve the exchange of ideas and information and reduce workflow bottlenecks. The result is a productive and engaged workforce able to innovate and thrive during changing times.

8 min read

When my daughter was 17 months old, she discovered a superpower: the word “Why?”For the next two years, it was her response to almost everything.

11 min read

I have a friend who often finds herself at the mercy of her emotions. Recently, she called me to rehash a confrontation she’d had with a group of...

9 min read

True leadership presence isn’t a performance or a set of charisma hacks; it is the felt experience of who you are being in the room. By cultivating...

Trust is often easy to build within teams.

With the rate of change and uncertainty in the world, CEOs think about trust regularly – no matter the size of their organisation.

Jane leads a team of 30 software programmers for a large insurance company. After months of slavishly working on a new sales tool to promote to car...