5 min read

Why Great Leaders Thrive When Good Ones Fail During a Workplace Crisis

Implementing change in the workplace often creates pressure, uncertainty, and emotional reactions - especially during a workplace crisis. Successful...

Develop leaders, strengthen executive teams and gain deep insights with assessments designed to accelerate trust and performance.

Transform how your leaders think and perform with keynotes that spark connection, trust and high-performance cultures.

Explore practical tools, thought-leadership and resources to help you build trusted, high-performing teams.

Trustologie® is a leadership development consultancy founded by Marie-Claire Ross, specialising in helping executives and managers build high-trust, high-performing teams.

7 min read

Marie-Claire Ross : Updated on October 7, 2020

Years ago, an aspiring general manager had the misguided idea that reducing biscuit purchases would enable a hospital to save around $3,000 a year. The thinking was that nurses had two biscuits during morning tea and they could change to one biscuit in the morning and one in the afternoon. Alternatively, they could just skip afternoon biscuits. After all, wasn’t it enough to just have biscuits in the morning?

Unfortunately, the nurses didn’t see it that way. What they saw was that they were being treated unfairly, so they refused to work any overtime that was not compensated. Nurses had been working longer than their allocated shift, but after “biscuit-gate” they charged for everything. In the first month, it cost the hospital $250,000.

When leaders put profits before people, they can very quickly destroy a high-trust culture, where employees are happy to work above and beyond what is expected of them to fulfil the company’s purpose. The result is a low-trust environment where employees complain and argue about pretty much anything. In other words, it’s the kind of place where no-one gets out of bed wanting to go to work.

Where leaders get it wrong is that they believe they can make a small change and it won’t matter. But here’s the thing about humans. We are wired to notice small changes. We’re great at realising that an air conditioner has just switched off or our black wearing colleague has suddenly changed to wearing colour. At the same time, we also crave certainty and the ability to predict what’s going to happen in the future. In other words, we don’t like change much. What looks like an insignificant thing to a new leader, can be a massive issue for employees who have become used to a type of coffee bean or even a particular brand of tea.

At the extreme end, if that change takes advantage of employee’s goodwill, like with the hospital example, it can have disastrous consequences to the culture. It signified leadership that was out of touch with how employees made their organisation great.

But even other changes that don’t actually take advantage of employees can equally be damaging to culture. When it comes to making a change at work, from something as small as providing employees with Christmas gifts right through to restructuring how the company does business, it all starts at one place. That is, with leaders actually taking the time to understand and care about their people. This can be difficult work. If you get it wrong, employees can quickly spiral into cynicism and suspicion. Here are three rules about human behaviour that affect every single little (and big) change at work:

When it comes to fairness, we might like to believe that we are being rational, but the truth is that our perceptions of fairness are governed by complex emotions. These emotions can be highly charged and emerge over time through our social experiences with others. Little wonder that beliefs on fairness can expose a hotbed of pent-up emotions within most organisations.

Research shows that at work, where people are more sensitive to inequalities, increasing the perception of fairness and reducing unfairness will promote satisfaction and wellbeing. This can be easier said than done.

One of the most common complaints from employees is a lack of trust in leadership or management. What employees fear is that their organisation is out to make money and doesn’t care about people.

Why trust is so important is that every employee, and I mean every employee, wants to know that their boss and the organisation cares about them. That they’re doing a good job, they’re appreciated and that they’re not going to get fired. Where there is low trust, you have a high-stress culture. People are anxious and they’re worried about how long they will keep their job and be able to pay their mortgage. They start misunderstanding and misinterpreting the signs around them – so that little things become really big in their mind.

Why do you think nurses were so incensed that their biscuits were removed? It’s because it was a sign that management couldn’t be trusted. That management cared more about keeping costs down, than keeping them happy. That they weren’t appreciated enough and their gesture of working overtime, without pay, to provide excellent care for patients, was ignored.

Trust gets built slowly over time and can be devastated in an instant. In most cases, where employees go on strike, such a severe reaction never occurs in isolation. Even small actions, over a period of time, can foster a low-trust and dysfunctional culture into overwhelming fear and anxiety.

A high trust culture buffers an organisation from potential strikes and employee suspicion and misinterpretation of motives. Cultures with high trust don’t spiral out of control with one seemingly small misdemeanour.

For too long there has been a mismatch between what science knows and what business does. In the book, Drive, by Daniel Pink he lays out the case that humans are intrinsically motivated and not extrinsically. We have an inherent tendency to seek out novelty, challenges, extend our capabilities, explore and learn. Yet, most organisations are based on an old paradigm that work is boring and people need to be coerced into doing it.

The truth is people are the happiest when they’re doing work they enjoy, making an impact and receiving appreciation. Ironically, when you reward creative and non-routine jobs, performance drops. That’s because people are focused on the reward and not actually on doing a good job. Rewards can actually harm performance. Yet, most companies, who wish to show their appreciation to their staff (or improve employee engagement), innocently throw out rewards, not realising they’re hampering performance. And causing unintended issues in the future.

The result? Employees start wanting more and even complain when they’re given a reward. As one General Manager said to me “We decided to give everyone $200. Rather than be happy or thankful, people ask “Why $200? Why not $500?”

And you can’t go back. If you give people biscuits – you will always have to provide biscuits. If you give people an Easter basket with eggs, you will need to do it every year (with everyone receiving the same size and number of eggs, remember, no favouritism). Rewards put you at risk of fostering a culture of entitlement because it increases expectations. No matter what you do, people will want more. Unfortunately, an entitlement mentality leads to a feeling of betrayal even when the company has been trustworthy all along.

When employees hate their jobs, perks won’t keep them. In fact, those perks create even more problems, as it’s seen as another attempt to force people to enjoy their work, without addressing the core issues at play. If leadership is distrusted, rewards are even viewed as a cynical exercise that only creates more distrust. The result being workers putting out their hands for more.

Instead, rewards that improve performance long term are always unexpected. If you want to reward your team, take them out for lunch after they have successful completed a project and make it clear why you did it. But don’t do the same thing next time (if at all) or even let them know there is a reward coming. Keep them guessing. Never let them know beforehand there is a reward (it will deteriorate performance) or alert them to a potential reward (it causes uncertainty). If you do decide to introduce a reward, say a present from the Easter Bunny, just realise you will have to keep doing that ad infinitum.

When humans are faced with uncertainty, we are motivated to reduce it. It’s one of the few things we subconsciously like to get back into balance without even realising it.

We all differ in our ability to tolerate ambiguous and uncertain situations. Some of us manage joining a new team pretty well or our company relocating. While others are filled with fear and anxiety.

Yet, even those who cope well under uncertainty are impacted negatively. A recent study from Wharton School found that during uncertainty, even those who cope well, are more likely to prefer practical and familiar ideas. The result is that it negatively impacts innovation as we stick to the status quo.

If you were an alien, looking down at workplaces, you’d be forgiven for thinking most employees are self-serving, greedy, immature, fearful and a little bit precious. The answer is yes they are, but we’re all like that. Even leaders. Even you. I remember my boss in my first full-time job arriving at work, slamming his office door and sulking in his office for an hour. The reason? Someone had parked in his car park.

Change begins with understanding. And it always begins with empathy. It’s easy to laugh at childish behaviour, but if you’re not at the same level as people, if you can’t empathise with their unique situation, then you can’t possibly motivate them to change.

Leaders need to be able to speak to people’s current struggles and challenges. They need to be able to address and rebalance people’s fear of uncertainty. If employees are trapped in the weeds because they’re annoyed that their boss ignored their new suggestion, then you can’t motivate them with a grand vision.

Likewise, if you want to introduce a change, even one as small as taking away biscuits, then leaders need to let people know why. Reducing costs might be important to management, but they’re not to employees unless their job is at stake. High trust organisations excel in their ability to talk openly about issues. They’re able to get everyone to unite together and work towards solving problems.

If the general manager at the hospital had discussed the need to reduce costs because say, they had a costly insurance expense due to an unfortunate patient injury, then employees would have been more likely to pull together and get the hospital back on track, knowing it was in the group’s best interests. Having a conversation might have also alerted him that the biscuits were really a tacit exchange of free overtime.

But introducing a change, without explaining the reason why and the benefits to employees (or hardship), always has the potential to cause outrage. Even to those who don’t really like biscuits.

Image Credit: Freeimages.com/Jenny Mespel

5 min read

Implementing change in the workplace often creates pressure, uncertainty, and emotional reactions - especially during a workplace crisis. Successful...

7 min read

Navigating difficult conversations at work isn’t just a “nice to have” leadership skill – it’s the fault line that often separates healthy,...

8 min read

When my daughter was 17 months old, she discovered a superpower: the word “Why?”For the next two years, it was her response to almost everything.

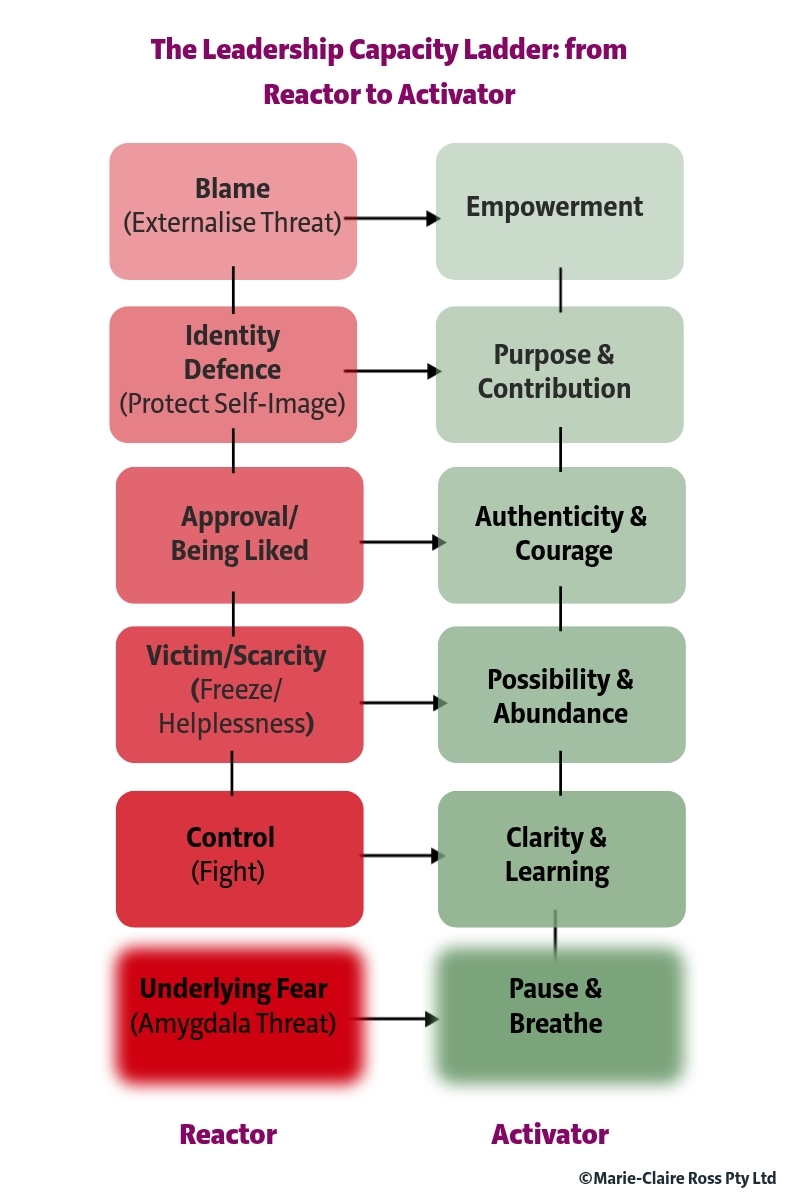

According to the Hoffman Institute, 90% of our reactions are emotional. In fact, our emotions respond 400 times faster than our intellect.

One November evening in 1987, commuters were busily rushing home from work on the London Underground.

6 min read

For 19 years, Greats Places to Work and Fortune magazine have been printing The 100 Best Companies to Work For list. Surprisingly, the...