8 min read

Beyond the "Why": 5 Coaching Secrets to Unlock Curiosity in Leadership

When my daughter was 17 months old, she discovered a superpower: the word “Why?”For the next two years, it was her response to almost everything.

Develop leaders, strengthen executive teams and gain deep insights with assessments designed to accelerate trust and performance.

Transform how your leaders think and perform with keynotes that spark connection, trust and high-performance cultures.

Explore practical tools, thought-leadership and resources to help you build trusted, high-performing teams.

Trustologie® is a leadership development consultancy founded by Marie-Claire Ross, specialising in helping executives and managers build high-trust, high-performing teams.

7 min read

Marie-Claire Ross : Updated on January 12, 2021

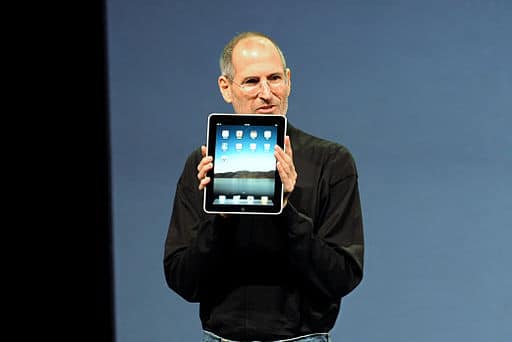

Have you ever wished you could have worked alongside some of the world’s best CEOs? How about the chance to have worked alongside Steve Jobs? Closely watching his every move so you could model the behaviours you admired. Or what about working with a creative genius such as John Lasseter, the Chief Creative Officer at Pixar who created Toy Story and Cars? What do you think you would have learned? How do you think it would have shaped your leadership style?

Introducing Ali Rowghani, a partner at Y Combinator (one of the world’s most powerful start-up incubators) who has had a corporate life most of us can only dream about. He has had the exceptional luck of having worked alongside Steve Jobs, Ed Catmull (Pixar’s founder), John Lasseter (Pixar’s Chief Creative Officer) and Bob Iger (Disney’s CEO).

So what did Ali Rowghani learn from all of these amazing leaders? While he would be the first to admit that they were extraordinary people, he found that their leadership style was completely different including both their approach and even temperament. Steve Jobs was infamous for brash behaviour, Ed Catmull was an introverted scientist, John Lasseter an extroverted artist, while Bob Iger was genteel and diplomatic.

But his main insight was astonishing. Even though they each had different leadership styles they all had one thing in common – the ability to build trust with the people around them.

Each excelled in three common areas which Ali Rowghani credits as three leadership traits that are the foundational elements behind great leaders. Without them, he believes you can never be a great leader.

Let’s take a look at each of these traits and the science that back it up, as well as some of my experience working with leaders to build trust.

According to Rowghani, leaders are better at communicating when they spend a lot of time thinking about what they believe is truly important for their organisation. They spend hours thinking, writing and planning internal communication.

In my experience, having spent 12 years directing and coaching CEOs and executives on giving a speech to camera, you can quickly separate brilliant leaders from the ordinary just by sticking a camera in front of them. Great leaders speak concisely and thoughtfully. They know what to say and how to say it. As a director, no matter how many times I persuaded them to change the content or say it to the camera again, their words came together seamlessly with a message that not only touched me but in the end their employees. They were thoughtful, welcomed feedback and you could tell had spent a long time considering how to best communicate the content to their people, no matter who they were. They were open to a frank and honest discussion on how to deliver and improve the content. Even better, they were easy to work with.

On the other hand, poor leaders were frazzled and demanded their safety leader or marketing manager write the speech for them (bad idea). Often, they had spent no time rehearsing (or thinking about) the content, so when they sat in front of the camera, they were anxious. Really tragic ones blamed everyone around them for their inability to synthesise a message.

Then, there were those who were happy to be directed but couldn’t drop their penchant for overly long and complicated sentences. Despite their friendly and open demeanour, precision in language (and thought) eluded them. Their ideas were all over the place and you knew they needed to think more about the topic. Where are those CEOs now you ask? Of course, they are no longer CEOs or they have been demoted to a less senior position.

If a CEO can’t communicate the strategy in a convincing manner, their influence literally stops at their next direct report. According to Donald Sull’s research in Harvard Business Review, less than one-third of executives can recall two priorities out of five. This keeps dropping the further down the hierarchy you go – with 55% of middle managers surveyed able to name one of their company’s top five priorities, with a meagre 16% for frontline supervisors and team leaders.

Employees are drowning in information, but are crying out for wisdom. They want leaders who can paint a vivid picture of the future and help them see how to get there. Yet, without people understanding why they need to follow a strategy and how it relates to them personally, and the organisation, time and effort is wasted on meaningless strategies and goals. When employees become confused about the vision, they will lose interest in achieving it and often will decide to not follow their leader with the commitment required for success.

Furthermore, high-trust leaders also communicate with integrity and are totally transparent and honest – refusing to sugarcoat the potential roadblocks and challenges ahead. They think clearly about the future and move their enterprise to the right place, in terms of product, sales, and people. All the time honestly assessing whether their predictions about the future are accurate. They understand that clarity equals speed.

As Rowghani advises, high trust leaders spend hours getting their message right and chunk it down into three easy to understand items.

2. Judgement about People

One of the important insights from Rowghani is that brilliant leaders have great intuition about people, particularly when it comes to selecting people to bestow power and responsibility. This ability extends to seeing hidden potential or detecting when ambition exceeds ability. They also fix hiring mistakes promptly if the employee is not coachable.

As the ex-CEO of a small video communications house, one of the things that took me a while to learn was how to employ the right people for the business. But my biggest faux pas in hiring was that I was too trusting of people, believing they had certain skills when they really didn’t.

That all ended when I used a more strategic approach to assessing whether to trust a person. While I agree with Rowghani that leaders need to be really good at judging who to trust, I disagree about following your intuition. I might consider myself an intuitive person, but throw in some hidden biases and a few filters and my hiring decisions were out of whack.

How we trust people is determined by our psychological makeup. Those who are hesitant to trust make decisions that put them at risk of missing out on opportunities, blocking out creative contributions, micromanaging others and creating a sea of distrust around them. While those who too trust easily put themselves at risk of fraud, incompetent employees, missed client deadlines and toxic employees causing havoc. Don’t sideline trust judgements just for recruiting. How we trust determine how we build trust with those around us whether it be a direct report, the CEO, the board or within teams.

The Evaluation to Trust model that I use and teach others, helps determine how much work is required to build trust with particular people but also assesses how trustworthy they are in the first place and whether it’s worth continuing the relationship.

More importantly, it gives you the science behind making trust decisions and with practise, you get really, really good at it. Unfortunately, no business school teaches leaders how to judge, rely or build trust. We do it by gut feeling and often fail to do our due diligence to gauge a person’s trustworthiness. We rely on a limited schema to judge trust and then get shocked at betrayal.

What has been interesting when coaching leaders how to use the framework is that their biggest takeaway is when they have reflected on their own behaviours and realised that they had been acting in a way that was reducing trust with their boss or a direct report. By extending trust to those they felt didn’t trust them, their results improved dramatically and quickly. This leads nicely into the next point.

3. Personal Integrity and Commitment

What Rowghani discovered is that great leaders have exceptional personal integrity and commitment to their mission. He termed integrity “as standing for something meaningful beyond oneself rather than being motivated by narrow personal interests.” They also exhibited what I would label trust behaviours – admitting when they made a mistake, avoiding favouritism, being open to feedback and avoiding conflicts of interest.

I agree totally with Rowghani with these points. The only suggestion I have is that we break these down more, so we can understand it at a deeper level.

The first one is a dedication to the mission is really all about a focus on purpose rather than profits. This provides employees with the context they need to understand how their work makes a difference to the world. It also lets everyone know – from employees through to customers – how much you care, which in turn makes them less likely to believe the organisation and you only care about making money. As Rowghani points out, it’s all about showing that you are not coming from an energy of self-interest.

This is what every leader needs to be able to do because, without that, employees will distrust you if they know you will put yourself first. People will only follow a leader who puts the interests of the tribe first, rather than their own. From my experience, leaders who can connect their organisational purpose to a social benefit are more motivating and influential to employees (5 Reasons Why Mission-Driven Leaders are the Most Successful). It’s the first step in being a clear communicator.

The second point is that building trust with others is all about exhibiting the right trust behaviours. There are literally hundreds of them if you isolate them all.

In my work and research, what I have found is that high-trust leaders understand trust at a more comprehensive level. To gain someone’s trust, we need to understand the other person and what trust means to them. Assuming that by treating people in the way you want to be treated is incorrect. The real learning comes when we realise we need to treat people the way they want to be treated and this means how they want you to build trust with them.

“We see the world as we are, not as it is. Some never awaken.”

Anais Nin

Where high-trust leaders really differ is that they have done the hard work to really understand what trust is all about. But more importantly, they are self-aware and can reflect on their behaviours and evaluate when they acted with trust and when they didn’t. And then, they DO SOMETHING about it. They accept that everyone is different and they customise their connection with each person on an individual basis rather than a generic basis. They live by personal values making it easy for them to connect others to the organisation’s values. They know themselves and they aren’t afraid to admit when they have made a mistake.

As Rowghani asserts, most leaders understand the science of building trust. They understand the operational requirements of communicating strategy clearly and making the right choices when hiring and promoting.

But where they fall down is the art of trust.

In my experience, this is the emotional side of running an organisation. Many leaders are great at making their numbers. It’s often what got them promoted to the top job in the first place. But the danger is that in creating efficient, scalable business processes the meaning of work gets lost.

Leaders need to communicate to the part of the brain that manages trust – the mammalian or limbic brain. This old part brain is not a thinking brain, but a survival brain, designed to keep us alive in times of danger. It is responsible for our feelings (such as trust and loyalty), decision making and handling stress.

But the real kicker is that it has no capacity for language. The only way to get through is to start with emotion – the why. Why the change was required and the thinking behind the decision. Why you want people to follow this process and the thinking behind it. This is why purpose is so important in communication. The truth is people are not as interested in information if they don’t know why. It gets them to lean forward and makes it a much higher priority in their life. That’s why leaders who anchor to the purpose in their communication are such inspiring leaders.

In summary, building trust in an organisation all starts with leaders who are intentionally wanting to build trust in every interaction. They also expect this behaviour from others, ensuring that trust cascades throughout the organisation. Over time, it eventually becomes embedded within the company creating a high-trust culture where people love to work and be part of something bigger than themselves.

8 min read

When my daughter was 17 months old, she discovered a superpower: the word “Why?”For the next two years, it was her response to almost everything.

11 min read

I have a friend who often finds herself at the mercy of her emotions. Recently, she called me to rehash a confrontation she’d had with a group of...

9 min read

True leadership presence isn’t a performance or a set of charisma hacks; it is the felt experience of who you are being in the room. By cultivating...

-1.jpg)

There is no doubt that COVID has changed our workplaces forever. Things will never go back to business as usual. All of us have been changed -...

When it comes to training staff on safety or procedures, one of the biggest problems many of our clients talk about is the difficulty of training...

Mediocre companies will often tell you they have a great culture, but when you question them on what makes it wonderful, they provide you with bland...