7 min read

Navigating Difficult Conversations: 7 Steps for Emotionally Intelligent Leaders

Navigating difficult conversations at work isn’t just a “nice to have” leadership skill – it’s the fault line that often separates healthy,...

Develop leaders, strengthen executive teams and gain deep insights with assessments designed to accelerate trust and performance.

Transform how your leaders think and perform with keynotes that spark connection, trust and high-performance cultures.

Explore practical tools, thought-leadership and resources to help you build trusted, high-performing teams.

Trustologie® is a leadership development consultancy founded by Marie-Claire Ross, specialising in helping executives and managers build high-trust, high-performing teams.

3 min read

Marie-Claire Ross : Updated on February 3, 2025

A common statement made about trust is that you need vulnerability. Building trust requires team members to be vulnerable with one another. That means confess to mistakes, talk about their fears, share authentic personal stories and ask for help.

In a workplace, organisations often encourage people to trust each other by sponsoring lunches and virtual meetings. And while it seems reasonable to expect that the more people meet with each other, the more trust will blossom, it is not actually correct. We need to go deeper in our interactions with each other.

Dr Jeff Polzer, from Harvard Business School, undertook a study where complete strangers had to ask questions of one another. Group A participants were asked standard personal information sharing questions such as "What was the best gift you received and why?" While Group B participants had questions that were uncomfortable to answer such as "Is there something that you've dreamed of doing for a long time? Why haven't you done it?" Group B questions were awkward and generated confession. They also melted the ice between strangers and generated deeper connections. But it did something else that was extremely powerful.

It created genuine vulnerability - allowing Group B strangers to feel 24% to form more meaningful connections than those in Group A. In fact, one Group B couple ended up getting married. Group A participants asked questions that allowed them to stay in their comfort zone. In other words, the standard types of questions we ask people at work functions.

But this is where it gets really interesting.

We often assume that vulnerable leadership is going to make us feel ashamed in some way. That through emotional exposure, we are putting ourselves at risk of exploitation. We fear that people will see us for who we really are or make fun of us. So many of us avoid being vulnerable because we worry that it will negatively impact our professional boundaries.

I am not going to lie - there is risk with overly sharing personal secrets. Especially, with those who do not have out best interests at heart.

Yet, the benefits of being able to express true vulnerability in a workplace are huge. Particularly, within a team.

When leaders admit to having weaknesses and ask for help, it sets the behavioural tone for others. Enabling team member to brush aside their insecurities, trust one another and get to work. In fact, if there is no vulnerable moment, people will default to covering up their weaknesses resulting in dysfunctional interactions and work quality.

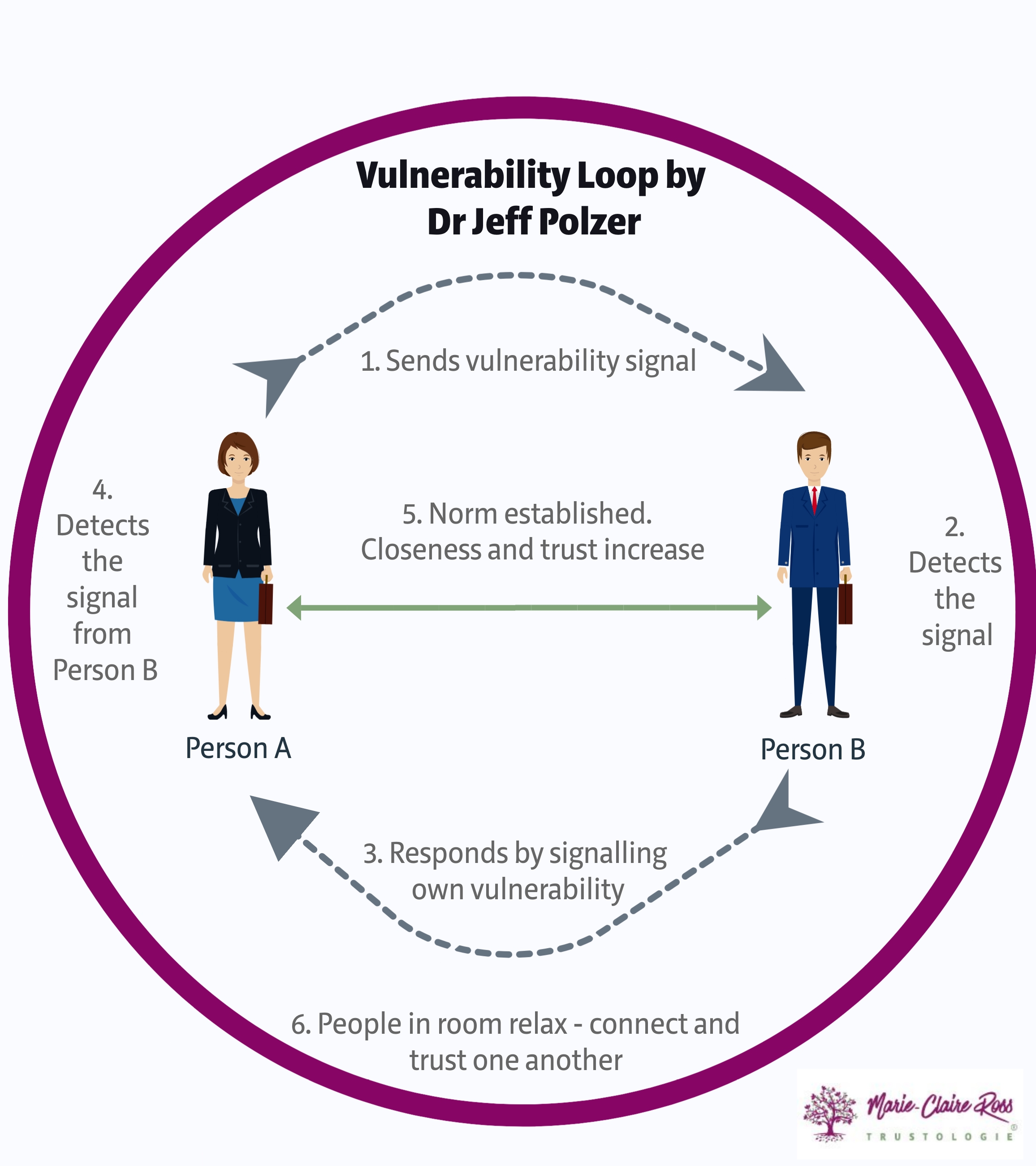

But here's the catch. Dr Polzer's research found that vulnerability isn't about the sender. It's all about the receiver.

And this is what we often get wrong. A common complaint by employees is that their leaders need to be more vulnerable. And yes - leaders do need to be humble and ask for help, in order to build trust. But few people ever look at themselves and consider whether they are enabling those around them to be vulnerable.

If the second person pretends they don't have any flaws or ignores the sender's vulnerable comment, it creates distrust in the team impacting team dynamics (especially if the leader ignores the signal).

In fact, Polzer has become skilled at observing the moment of truth when effective vulnerability travels through the group. He says, “You can actually see people relax and connect and start to trust.” Polzer calls it a vulnerability loop that transfers trust to other people in the room, just like a virus. It creates a culture of trust in high-performing teams.

How we react to other people disclosing personal information is critical. Not just by leaders to their people, but vice versa. If we aren't taught how to empower those around us to share insights and fears, we are contributing to reducing psychological safety.

The outcome is that people will fear taking risks in the group and will shut down further contribution and commitment.

Effective leadership requires leaders to not only create a safe environment for people to talk about their concerns, but to also model being vulnerable and encouraging others in the team to do the same. Vulnerable leaders congratulate those who dare to show emotional vulnerability in the team.

This reminds me of an executive from a global company who told me how at the end of a leadership team meeting he disclosed he had cancer. The CEO said nothing. The other executives also said nothing. After less than a minute of uncomfortable silence, but what felt like an eternity, the CEO closed the meeting. Ignoring one of his key executives who was not only fearful about his health but who was now more fearful about his perceived value in the team. For many years, that executive (who survived cancer) still feels sick recalling the response. And shame for disclosing a weakness. He resigned earlier than he had planned as that episode continued to haunt him and question his ability to trust his CEO and peers.

This personal disclosure could have been a wonderful opportunity for the CEO to have encouraged genuine connections within the high-performing team. It would have also powerfully built mutual trust, reduced the potential for mental health issues and provided support for someone in need. Yet, that important opportunity to form deeper relationships and help someone was lost.

So the next time you hear someone quip about how trust and vulnerability are important ask them "How do you respond when a colleague bravely offers a vulnerable moment?" Because that is KEY.

If we believe that a culture of vulnerability is important, then we need to learn how to safely allow others to be vulnerable. It's a two-way. The concept of vulnerability is so much more than just disclosing our own personal frailties. Authentic leaders realise it's about making it safe for others to do so, so that team members feel seen, heard and valued.

7 min read

Navigating difficult conversations at work isn’t just a “nice to have” leadership skill – it’s the fault line that often separates healthy,...

8 min read

When my daughter was 17 months old, she discovered a superpower: the word “Why?”For the next two years, it was her response to almost everything.

11 min read

I have a friend who often finds herself at the mercy of her emotions. Recently, she called me to rehash a confrontation she’d had with a group of...

Jane leads a team of 30 software programmers for a large insurance company. After months of slavishly working on a new sales tool to promote to car...

One of the interesting things I find when it comes to safety is that some safety professionals (some, not all) like to play bad cop when it comes to...

We all know how wonderful it is to be around positive people. Optimism is contagious. People are naturally drawn to visionary leaders who paint an...