11 min read

4 Practical Strategies for Better Emotional Management in the Workplace

I have a friend who often finds herself at the mercy of her emotions. Recently, she called me to rehash a confrontation she’d had with a group of...

Develop leaders, strengthen executive teams and gain deep insights with assessments designed to accelerate trust and performance.

Transform how your leaders think and perform with keynotes that spark connection, trust and high-performance cultures.

Explore practical tools, thought-leadership and resources to help you build trusted, high-performing teams.

Trustologie® is a leadership development consultancy founded by Marie-Claire Ross, specialising in helping executives and managers build high-trust, high-performing teams.

4 min read

Marie-Claire Ross : Updated on July 5, 2022

Imagine a management team that has had a tough few years - dwindling revenue, archaic systems and processes that need an expensive overhaul and unhappy customers. A new CEO is brought in to steady the ship. One of his first jobs is to refresh the leadership team, stabilise losses and improve productivity.

The result is a fresh team comprising of new team members and a couple of existing executives that are part of the old guard.

The new executives are on a journey to transition from focusing on their technical skills, to getting the best out of their team members and developing an organisational perspective (rather than a departmental perspective). They are green and have a steep learning curve, in a tough operating environment.

While the existing team members have kept their senior leadership roles because they know all the systems, customers and what has worked and what doesn't. They are seasoned, high performing executives who set high standards for themselves and others.

The problem is that the high performing executives have a low tolerance towards those that don't perform at their level. They discount the fact that their new colleagues are learning the ropes. Instead, they regularly stress test their new peers to see if they are any good - challenging their decision-making, questioning their abilities and criticising their performance. They want to be convinced that their new colleagues are up to scratch. Yet, their confrontational methods only make their new peers flustered and unable to answer their questions appropriately. Consequently, the existing executives lose confidence in their new colleagues. They refuse to co-operate with their new team members and wield their influence in the team, and with the CEO, to fuel doubt about their new colleagues.

Meanwhile, the new members realise they can't trust the existing executives. They retreat from dealing with them and form alliances with other new team members. Silos form within the leadership team creating noticeable issues with cross-functional collaboration.

In the book, The Infinite Game, by Simon Sinek, he asked a group of Navy SEALs how they choose who gets to go on an important mission.

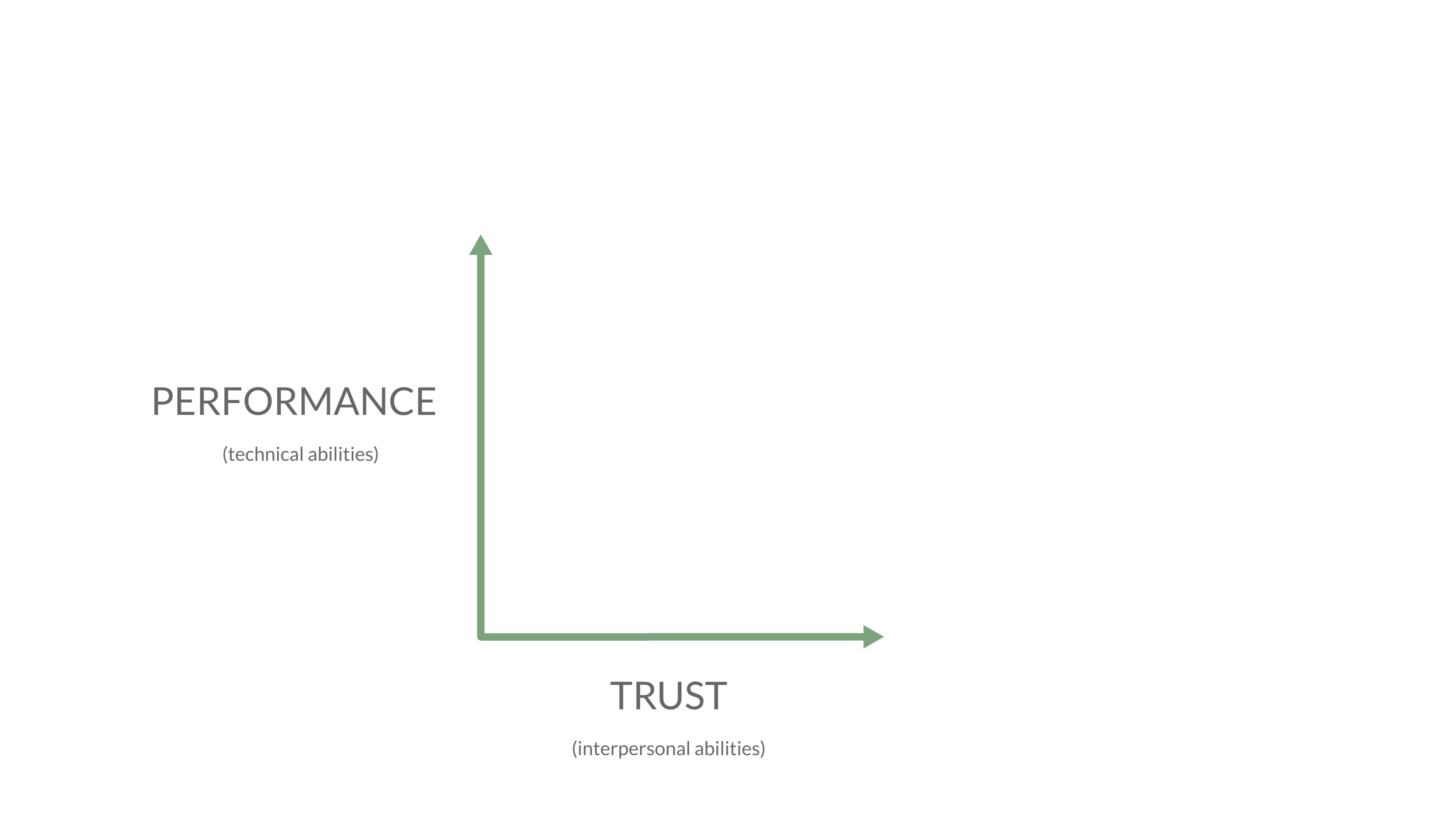

The SEALs drew him a graph with PERFORMANCE on the y axis and TRUST on the x axis. Their distinctions between the two labels was that PERFORMANCE referred to performance on the battlefield and TRUST was performance off the battlefield.

You can extrapolate that to a corporate environment as PERFORMANCE being technical skills and capabilities, while TRUST are the interpersonal skills. In other words, how we treat others, communicate with people and influence them.

As you would expect, no-one wants the low performer/low trust person on their team. Everyone wants the high performer/high trust person on their team.

But not all high performers are equal. What the US Navy learnt was that when you have a high performer with low trust they were a toxic leader and toxic team member.

Counterintuitively, they discovered it was better to have a medium performer with high trust and even a low performer with high trust, than a high performer/low trust leader.

Most organisations are adept at measuring performance, but poor at measuring a person's trustworthiness. Trustworthiness is more valuable than performance. Yet, we value job proficiency.

In organisations, high performers/low trust employees are everywhere and commonly promoted and rewarded. In my work with companies around the world, employees will often tell me their disappointment at a high performer/low trust employee being promoted to a leadership position. A common remark is "You see examples of horrible bosses in the system were being promoted for getting the job done at the expense of their team’s mental health. You have to wonder if we have the right leadership that cares about the health and safety of their employees.”

What's striking is that pretty much all employees can agree on the high performers/low trust people. As Simon Sinek outrageously says, you can find high performers/low trust trust staff by asking employees "Who's the asshole?" They will always point to the same person.

Likewise, employees can all nominate the colleague they can trust - the one they know has their back. Employees who create a trusted team culture, while not necessarily being a high performer, but whose behaviours elicits high performance in others. The very ones that needs to be promoted to leadership positions. To find them, you just have to ask employees "Who do you trust more than anybody else? Who do you know will be there when the chips are down?"

Frequently, in my work with leadership teams, a CEO will complain about an executive who isn't performing at the right level, while dismissing their ability to create a thriving team environment. Measuring a leader's performance on how they treat others is something that we have difficulty doing. We focus on the what they do (which is often more easily measurable and visible) rather than the how they do it. Yet, measuring these distinctions are critical to creating an effective company culture.

The damage that a high performer/low trust leader can do to an organisation is immense. Their behaviour is often abusive and focused on belittling others, in order to prove that they are better. Their behaviours might appear to support the organisation going forward, but this is to mask their self-serving behaviours. Even more detrimental is when their behaviours force medium performers/high trust leaders to leave. The very people that are critical to improving the organisational culture.

11 min read

I have a friend who often finds herself at the mercy of her emotions. Recently, she called me to rehash a confrontation she’d had with a group of...

9 min read

True leadership presence isn’t a performance or a set of charisma hacks; it is the felt experience of who you are being in the room. By cultivating...

13 min read

As teams return from their summer (or winter) break, you may notice subtle shifts in your team’s energy. Even if the end of year was positive, a new...

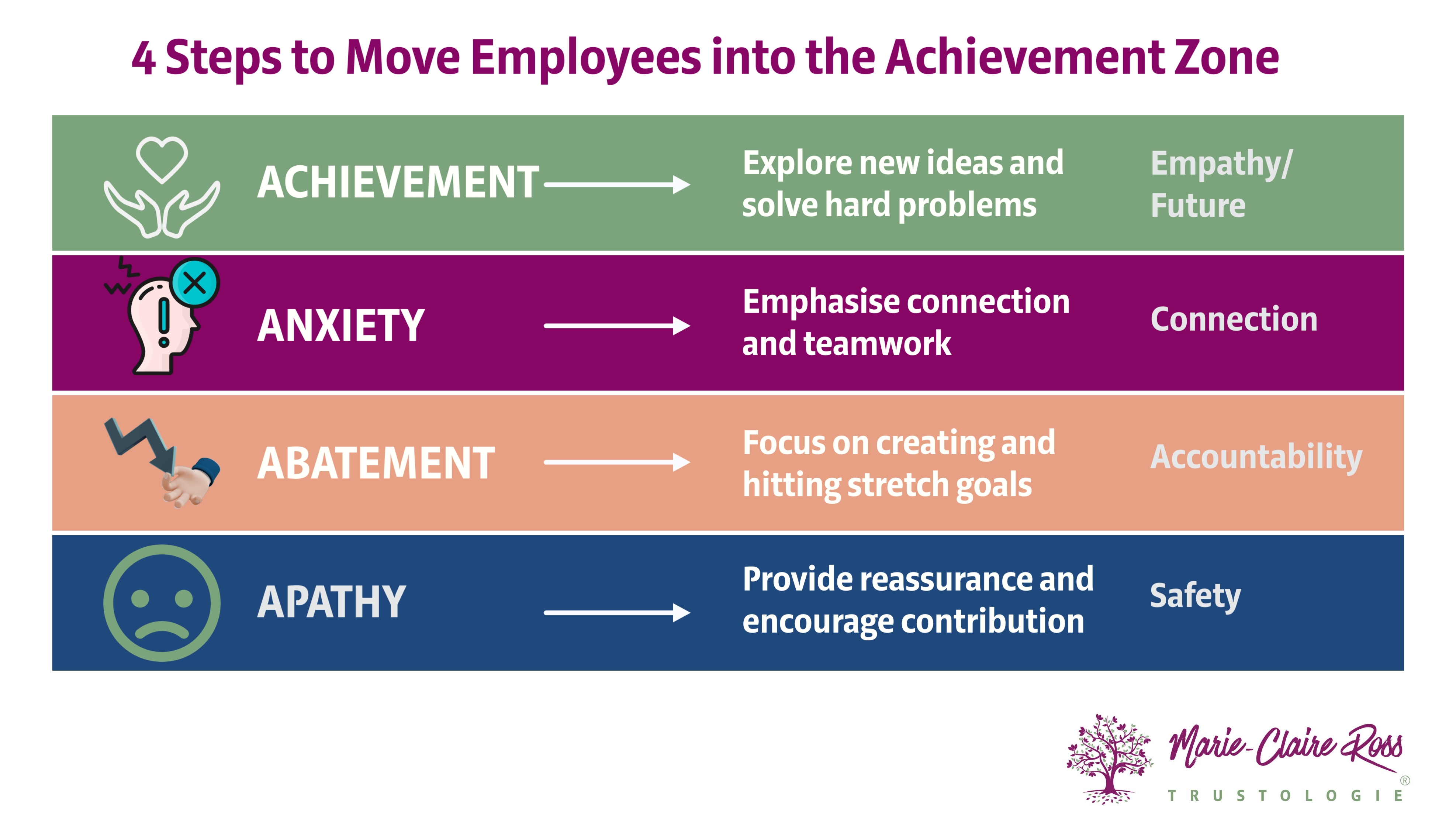

Jane leads a team of 30 software programmers for a large insurance company. After months of slavishly working on a new sales tool to promote to car...

In the pressure cooker business world we live in, change and uncertainty have become commonplace. No longer can organisations rest on their laurels....

Thanks to our biological programming our brains like certainty and feeling safe. When things change and we become unsure, we operate from our...